WHY SHOULD YOU CREATE COMICS FOR YOUR LESSONS?

Duration: 30 minutes

Objectives: The objective of this lesson is to introduce learners to the notion of educational comics, their benefits and advantages when created by the teachers to be included in the curriculum.

Desirable outcomes and competences:

|

You have entered the E-learning module of EdComix project. If you opened this lesson today, you are probably interested in discovering a new teaching tool: comics. First introduced in the classrooms in the 1940s, they have gradually fallen in disuse in the course of the 1950s. Since the 1990s, they are making new apparitions, both on the theoretical scientific scene and the practical scene, in the classrooms. The democratisation of the Internet allowed the release of a variety of new tools, useful to create comics without having to draw yourself. These tools are at the core of our project. Creating comics to use in an educative context has various advantages, for both students and teachers. Before walking you through some of them, let us briefly present you this module.

About the module and lesson plan

Throughout this module, we will walk you through everything comics have to offer in an educative context. The program is organized in 24 lessons, on specific themes, which will take you through the process of creating your own comics, step by step. We aim at giving you all keys and solutions to make you an expert in educational comics creation.

We will first introduce all the reasons why you should pursue this direction. Then, we will dive into practical content: what are comics? How to practically integrate them into your lesson plans and the curriculum? That said, we will look at digital comics creation and guide you through all the steps, that are: creating a narrative, storytelling, design, layout, and other comics specificities. In the last part of this module, we will tell you all about the online tools at your disposal and their functioning. Additionally, as we wish to offer you a comprehensive learning experience, we will finish by giving you tips and good practices to pass on your new knowledge to your colleagues and explain your approach to parents. The entire lesson plan is included below.

As you might have already noticed and will see throughout the lessons, we put a high emphasis on inclusiveness. Our idea is to help teachers create material fitting to the needs of students with learning disorders (thereafter SLD), that are dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, dysphasia, and dyspraxia. Explanations regarding these disorders are given in the third chapter of our Pedagogical guide (IO1) and in the lesson 5. But we will also touch upon other concepts related to inclusiveness, in particular regarding the representation of different groups.

Before proceeding, we would like to indicate some important points: this module is targeted to teachers in secondary education, therefore teaching adolescents from the ages of 11 to 18. You can also consider using it if you are teaching adults. However, when it comes to younger children, the process might require adaptations, particularly when it comes to the various exercises mentioned throughout this project’s outputs.

This module qualifies for 1 ECVET point (European Credit system for Vocational Education and Training), attributed following the quiz happening after these 24 lessons. Please contact your hosting organisation for more information concerning the possibilities linked to the completion of this module. More information about ECVET points can be found here: https://www.ecvet-secretariat.eu/en/faq-page.

At this point, you might be wondering why you should follow this module and create your own comics as a teacher. As promised earlier, let us explain some of the advantages of creating your own comics for English language acquisition.

Motivation and engagement

First and foremost, comics can be more motivating and engaging than other reading material. Traditionally considered as a hobby, in most countries few are the students who ever encountered them in their studies. Therefore, comics first appeal as a novelty. Second, they can be a great tool to make the classroom less strict and formal and encourage everybody to participate.

As it is argued in a blog article by Pixton (2017), “[…] storytelling, sequential art, and embellishment are naturally engaging, particularly to those who are growing up in a fast-paced world of social networks, gadgets, and an inescapable flood of super hero movies”.

Flexibility and adaptability

Comics offer flexibility. They have been and can be adapted to different subjects – from language learning to biology (some examples appear in our Pedagogical Guide, as well as in Lesson 4) –, to different age groups and to different types of learners.

Visual and spatial learners will benefit from the visual elements, verbal and linguistic learners from the text. Mathematical and logical learners will be helped by the logic of the story and the page organisation. Bodily and kinesthetic learners will be able to focus on facial expressions and characters’ positions. You will find out more in the first chapter of our Comics creation Guide (IO2).

When knowing the age, the learning capacities, and the level of knowledge of your students, you are in the best position to create comics adapted to your audience. You will be able to create a variety in the types of discourses, choose words and vocabulary appropriate to your lesson, use idioms or even slang, set up the story in an environment or decor fitting the topic taught.

Additionally, you should realise soon enough that creating comics to include in your lesson plan is, in reality, easier and less time consuming than it is to find the exact right strip in the exact right book. Indeed, the research for the perfect comic, fitting both your standards of vocabulary and subject, could be quite long if you are not familiar with this world. Even if you are, roaming through several albums to find the perfect catch could take a while. Creating them yourself is, therefore, the easy solution.

Improvement of various skills

You will cultivate an array of skills. Here is a list:

- Creating comics will boost your imagination and your creativity. Whether you design your comics yourself or ask your students to do so as an exercise, it will require imagination.

- Creating comics will enhance your storytelling and narrative organisation skills. Storytelling became a new marketing strategy in the last decade. It is used to engage buyers in the product sold. Stories convey meaning and purpose (Thompson, 2018). They help us organise and remember information and tie its content together (Hamilton & Weiss, 2005). Writing a story is the first step of comics creation. It comes before designing and organising the content into panels. You will find more details in lesson 13.

- Creating comics will increase your digital skills. It is understood that you will create most comics using the digital tools highlighted in Lessons 15, 19 and 20. By using those tools, you will be practicing drag and drop, add/remove elements, zoom in/out, as well as how to approach web content with a more critical spirit.

- Creating comics will develop design and aesthetic skills. Regardless if you decide to hand draw every strip or to use the online tools, you will put your design skills into practice, whether it is by drawing, colour matching or creating an attractive layout.

Upon finishing this first lesson, we would like to give you a last recommendation. Please keep in mind that you will face some challenges in your journey to create your own comics. You may face sensitivities regarding issues like gender, race, or religion, which you will need to approach with special care. You might lack time and feel a bit overwhelmed. This guide is made to make the process easier and quicker. In general, do not worry, all conceivable challenges are easily surmountable. We believe in you!

References

Articles

Hamilton, M., & Weiss, M. (2005). The power of storytelling in the classroom. In Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom (2nd Ed. pp.1-10). Katonah, NY: Richard C. Owens Publishers. Retrieved from https://www.rcowen.com/PDFs/CTS%20Ch%201%20for%20website.pdf

Websites

Pixton (2017). 10 Reasons to Use Comics in Your Classroom. Pixton Edu website. Retrieved from https://edublog.pixton.com/pixton-edu-comicsintheclassroom

Thompson, S. (2018, December 7th). The importance of storytelling in business, with examples. Virtual Speech. Retrieved from https://virtualspeech.com/blog/importance-storytelling-business

THE ADVANTAGES OF COMICS FOR LANGUAGE EDUCATION

Duration: 60 minutes Objectives: The objective of this lesson is to introduce learners to the benefits of using comics in general and specifically for language learning. Desirable outcomes and competences: By the end of the lesson, learners should be able to:

|

In the previous lesson, we have been over the reasons why you should create comics to integrate into your lessons. We highlighted the skills that you will gain or improve through that. In this lesson, we will discuss the advantages of using comics in the classroom, whether these are self-made or not.

This lesson will focus on using comics for language acquisition and especially English. Most of the techniques and resources described here and throughout the project can be adapted to both English as Native Language (ENL) and English as Foreign Language (EFL) courses. However, our target group remains mostly EFL teachers, and by extension, students.

Motivation and engagement

First, we must come back to motivation and engagement. These are two of the most significant advantages. Using popular comics and mangas might have a higher motivating effect than using your own creations, as students might already be familiar with the stories. Comics, some of their stories or characters might already be familiar to your students. Some might have read Tintin or Asterix books in their childhoods. Superheroes from American comics are more present than ever in the box-office, notably with the Marvel cinematic universe and the Avengers movies (CNN, 2012). Mangas and animes have been distributed in Europe since the end of the 1970s, but they have become less of a subculture from the end of the 2000s, with franchises such as Naruto or One Piece (Katelan, 2018). Additionally, one cannot fail to mention Pokémon, whose total revenue, media and merchandising combined, is still the highest within all media franchises worlwide. Initially released as a videogame, the story was quickly adapted to an anime and a manga, from 1997 and is still ongoing in 2020.

In that sense, using a strip featuring famous characters such as Pikachu or Iron Man might get you more engagement. However, this is not a reason enough to use only published comics. You will see in the next paragraphs and lessons that it is not as easy and effective as you might think. We have already been over the difficulty of choosing the perfect strip in Lesson 1.

Exercises

Comics offer an array of possibilities when it comes to traditional language classroom exercises. Any exercise you have doing before can be enriched by using strips, and more. For example, you could consider asking students to identify grammatical points in comics text, to list adjectives that describe comics characters, to finish a story told in a comic strip or to turn the comic’s direct speech to indirect.

Here are some additional examples of exercises, which are more specific to the comic medium:

- Comic jigsaw: take a one-page strip, cut it, and ask your students to put the story together.

- Translation of their favourite comic: Now, this could be done with their favourite book or novel. However, this exercise would allow you to have some insight into what characters and franchises your students like. Therefore, if at some point, you wish to use published comics in your lessons, rather than your own, you will have narrowed down the possibilities.

- Acting strips out: Comics can be an alternative to theatre plays, insofar they are already made of dialogues and use a more modern and up-to-date vocabulary. For example, you could find adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays to suggest ways to your students to act them out.

You will find additional examples of exercises in Lesson 9.

Comics can help teach cultural awareness

Language classrooms are a gateway to the study of other cultures. Cultural specificities and differences are often explained alongside grammar. Students learn how native speakers talk, live, and see the world, through typical idioms, foods, or movies. Comics can help with that. As a visual medium, they offer an alternative to films and series, they have the advantage to be less time-consuming and they are easier for students to refer to when they are at home.

How can comics teach cultural awareness? They depict real-life situations, which contain many cultural connotations (Brown, 1977). One can find several mangas illustrating day-to-day life in Japan, just as Hollywood’s TV series and movies do with the American lifestyle. Individuals reading many mangas might feel closer to the Japanese way of life and way of thinking – or at least feel like they understand it better.

Improvement of various skills

In the first lesson, we have been over the skills you might gain as a teacher creating your own comics for your students. It is time to dive into what skills students might acquire when working on and with comics. Here is a list:

- Using comics can help to sharpen students’ memory (Short et al., 2013) by giving the brain visual stimuli to associate with new words and concepts. This will prove particularly interesting in language learning, especially for vocabulary acquisition. First, because comics do not rely exclusively on words, like novels do. Second, because drawings are usually correlated to the text.

- Using comics can develop their reading skills. A study by Karap (2017) found that students’ ability to interpret the story, as well as their recalling abilities, were higher after learning through comics. In 2013, Basol and Sarigul’s study showed that foreign language learners reading comics outperformed students reading traditional formats in reading comprehension. It is an argument that often comes back: comics help reticent and struggling readers and change their attitude towards reading. A study by Whipple (2007) reveals that their interest in reading increases when faced with comics. Research suggests ‘that pictures presented alongside text facilitate comprehension by reducing the cognitive load of dense text’ (Meuer, 2018). Using comics will allow the reader to focus on important text aspects and eliminate the potentially confusing ones. Additionally, a study by Cimermanová (2015) found students more willing to use reading strategies such as deducing when reading comics than when not.

- Using comics can improve visual and multimodal literacies. Visual literacy is ‘the ability to recognize and understand ideas conveyed through visible actions or images’ (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Elsner and al. (2013) described multimodal literacy as “the ability to obtain, systematize, expand and link information from different symbolic systems”. Symbolic systems include written language, spoken language, and patterns of meaning that are visual, oral, gestural, tactile, and spatial. (Multimodal Literacy, 2018). Both visual and multimodal literacy are essential in today’s society. We are receiving constant visual stimuli, either from television, the internet, magazines’ advertisement, street panels, etc. Unfortunately, similarly to texts, images can be shaped and moulded to someone’s vision and thoughts. The ability to analyse them and to decipher their veracity is essential to avoid being a victim of false information (Elsner et al., 2013). Bringing comics into the classrooms is an excellent way to work on both skills, by analysing the drawings and their relation to the text and trying to deduce the author’s thinking and conveyed message.

- Last but not least, and with regards to the previous point, using comics can also enhance critical thinking. There is a lot to analyse and interpret in a single panel: literary details such as narration, setting, characterization, and symbolism, and visual elements including line, shape, colour, and contrast (Seelow, 2020).

This list contains only the most noticed and highlighted skills. Researching on the subject yourself, or even browsing through our different outputs, you might stumble upon several others that are not mentioned here for the purpose of conciseness.

Incidentally, it is safe to say that students will develop the same array of skills than you if you decide to let them create comics themselves. It will foster their imagination and their creativity, improve their storytelling and narration organisation, as well as their digital and design skills.

In the next lesson, we will go through the skills you need before engaging further in this module. You will quickly realise that this does not entail as much difficulty as you may think.

References

Books

Elsner, D., Helff, S. & Viebrock, B. (2013). Films, Graphic Novels & Visuals: Developing Multiliteracies in Foreign Language Education – An Interdisciplinary Approach, Berlin: LIT Verlag, Retrieved from https://books.google.com.cy/books?id=_bBdnqY19cUC&dq=+multiliteracies+comics&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Articles

Basol, H. C. & Sarigul, E. (2013). Replacing traditional texts with graphic novels at EFL classrooms. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 1621–1629. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.231

Brown, J. W. (1977). Comics in the foreign language classroom: Pedagogical perspectives. Foreign Language Annals, 10(1), 18–25. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1977.tb03072.x

Cimermanová, I. (2015). Using comics with novice EFL readers to develop reading literacy. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 2452–2459. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.916

Hayes, D., & Athens, M. (1988). Vocabulary simplification for children: A special case of “motherese”? Journal of Child Language, 15, 395–410.

Karap, Z. (2017). The possible benefits of using comic books in foreign language education: A classroom study. Képzés És Gyakorlat, 15(1–2), 243–260. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.17165/TP.2017.1-2.14

Meuer S. (2018). Using Graphic Novels to Increase Comprehension and Recall, MinneTESOL journal, vol 34 (2). Retrieved from http://minnetesoljournal.org/journal-archive/mtj-2018-2/reading-comprehension-through-graphic-novels-how-comic-books-and-graphic-novels-can-help-language-learners/

Short, J. C., Randolph-Seng, B., & McKenny, A. F. (2013). Graphic Presentation: An Empirical Examination of the Graphic Novel Approach to Communicate Business Concepts. Business Communication Quarterly, 76(3), 273–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569913482574

Whipple, B. D. (2007). Comic books: They’re good for you. (M.A.E.). Pacific Lutheran University, Washington, United States.

Websites

Katelan J-Y. (2018). How Manga conquered the World. CNRS News. Retrieved from https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/how-manga-conquered-the-world.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Visual literacy. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved July 9, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/visual%20literacy

Multimodal Literacy (2018, August 29th). Victoria State Government. Retrieved from https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/readingviewing/Pages/litfocusmultimodal.aspx

Seelow D. (2020, May 21st). Using Comics to Teach the 4 Cs. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/using-comics-teach-4-cs

‘The Avengers’ smashes domestic box office record for opening weekend (2012, May 7th). CNN. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2012/05/06/showbiz/avengers-breaks-record/index.html

Comics

Lee S. (1963). The Avengers #1 [Cartoon]. New York, NY: Marvel Comics

Kishimoto M. (2003). Naruto #1 [Cartoon]. Tokyo: Shonen Jump

Kusaka H. (2000). Pokemon Adventures #1 [Cartoon]. San Francisco, CA: Viz Graphic Novel

WHAT SKILLS DO YOU NEED?

Duration: 60 minutes Objectives: The objective of this lesson is to introduce learners with the skills they need to create their own comics and to use them in their classroom Desirable outcomes and competences: By the end of the lesson, learners should be able to:

|

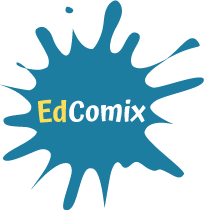

Following this overview on the advantages of creating and using comics in classrooms, we would like to finish this theoretical part by reassuring you on the skills you will need to create your own comics, before diving into facts and general knowledge. We have discussed the skills you might develop and improve throughout the process in the two previous lessons. Our objective in this third lesson is to analyse if you might already have some or most of the necessary skills.

Willingness to try

The first skill is not a skill, per se. It is a state of mind. Becoming proficient in comics creation takes practice and time. Therefore, the first thing you need is willingness to create something new for your students, together with a hint of willpower. Similarly to any project, these two are essential and will be your best ally. Do not be hard on yourself and do not expect a perfect outcome from your first effort. Keep pushing through, discover the digital comics creation tools, play around with the features… In any case, do not give up at the first difficulty. You will come through.

Basic digital skills

As you should have understood by now, our project’s idea is not to teach you to draw but to create digital comics. Therefore, you and your students need to be computer savvy. This is also the reason why we do not target teachers of primary education. Now, what does ‘to be computer literate’ mean?

- Being able to set up and turn the computer or tablet on and off.

- Being able to use peripheral devices, especially keyboard and mouse, but also printer and external storage devices, such as USB keys (Computer Literacy, 2017).

- Know some basic keyboard and mouse commands, such as copy/paste or undo/redo, which could help you save a lot of time. (James, 2012)

- Being able to connect the computer to the Internet, whether by WiFi or Ethernet (Computer Literacy, 2017). In parallel, computer literacy also implies being able to turn on and off your router and to plug it / connect it to your computer.

- Being able to open and use a web browser: open a website, navigate between website’s pages, use bookmarks and search engine, understand common error messages, etc. (James, 2012)

- Being able to identify some security and privacy basic issues, such as warning messages from antiviruses and web browsers. (James, 2012)

- Know how to create and organise folders, to find your way through your documents, to download and manipulate files and know some files extensions names and their usefulness. (Computer Literacy, 2017)

Do you feel like you can cross tick all or most of these competences? If yes, congratulations, you have a basic level in computer literacy.

Now, you will also need to be digital literate. Computer literacy is a big part of digital literacy. Therefore, no need to worry. Check out how many skills you can tick off the list below. Being digitally literate means:

- First and foremost, to be aware of your rights and obligations regarding intellectual property, copyrighted materials and how to reference properly (Stauffer, 2020). Throughout the creation process, you will use many resources, especially stories, pictures, and drawings that you might directly include into your own or get inspiration from. It is important to keep in mind that you will need references if – one day – you decide to publish your own strips online.

- To have a critical mind in front of the flow of offers and information online, to be able to analyse and evaluate their veracity. (Digital Literacy Skills, n.d.)

- To communicate clearly, maintain respect and build trust just as when communicating in person. (What is digital literacy?, n.d.)

- To be able to protect your privacy and the one of your students by knowing and teaching the importance of strong passwords and of checking settings (Stauffer, 2020)

Are you digitally literate? In this case, you can follow this module and start creating your own comics.

Throughout the next lessons, you might encounter notions, vocabulary, or skills that you do not have – YET – or that you are unaware of. If they are not in the list above, most of them will be explained. If not, please check the term and watch a short tutorial. None of the concepts we will explore should be too complicated to grasp.

Knowledge of the teaching content of English A2 and B1 levels

We mentioned in Lesson 1 that our project’s target group is EFL teachers of secondary education, therefore teaching students from the ages of 11 to 18 years old. This is an approximation, as students enter and leave secondary education at different ages, depending on the country.

We will focus on CEFRL levels A2 and B1, that roughly correspond to those teaching ages. CEFRL stands for Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, and is, as its name indicates, guidelines set up at the European level to determine the achievements of foreign language learners.

To achieve an A2 level, a student must be able to:

- Understand short sentences and the highest frequency vocabulary

- Read short texts and find information in simple everyday material, such as a restaurant’s menu

- Communicate in a direct exchange of information on familiar topics

- Use a series of sentences to describe his life in simple terms

- Write short simple notes on immediate needs. (COE, n.d.)

To achieve an B1 level, a student must be able to:

- Understand the main point of standard speeches, radio and TV programmes when the delivery is slow and clear

- Understand text with high frequency everyday language

- Deals with situations most likely to arrive when travelling and enter unprepared into a conversation on familiar topics

- Connect phrases to describe experiences and explain himself

- Write simple connected text on familiar topics. (COE, n.d.)

These guidelines are extracted from the Council of Europe’s self-assessment grid. You will find a more detailed version in each European language here. We will come back to this framework in Lesson 6 and explain how to create comics linked to these learning objectives in lessons 7 and 8. If you wish to consult official guidelines and settings examples, the Council of Europe also published an extensive list of illustrative scales, that you will find here.

Contemporary pop-culture

Additionally, but not compulsory, a basic knowledge of contemporary pop-culture will be an advantage, to create comics more attractive to your students. Indeed, you could – for example – conceive a scenario revolving around the most popular heroes of characters.

If you have no knowledge of the subject at all, a simple 15-minute internet search will give you the answers you need.

Misconceptions and impressions

To finish this lesson, we would like to come back on those skills you think you will need to create your own comics, but that are not a prerequisite. In this category fall the misconceptions on the required knowledge and competences, but also the skills you will learn throughout this module.

- Knowledge of the genre

This might be your first worry: facing students that have more knowledge than you on the subject. Do not worry, the next lessons will give you the required vocabulary and notions to get you going.

- Design skills

We understand that design skills might be the blocking factor in your path to comic creation proficiency. That is the main reason why we decided to focus on digital tools. Here again, what is important is a willingness to put your current design skills to the test. You will not have to use any paper or pen. Everything will be pre-drawn.

- Specific software

You will not need to know the functioning of complicated design software like Photoshop or Illustrator, used by professionals to generate comics nowadays. Everything will be done on easy, user-friendly, online software. We will elaborate on this in lessons 15, 19 and 20.

References

Websites

Computer Literacy. (2017, August 14th – last update). EduTech Wiki. Retrieved from http://edutechwiki.unige.ch/en/Computer_literacy

Digital Literacy Skills: Critical Thinking (n.d.). Webwise. Retrieved from https://www.webwise.ie/uncategorized/critical-thinking-digital-world/

James, J. (2012, February 6th). 10 things you have to know to be computer literate. Tech Republic. Retrieved from https://www.techrepublic.com/blog/10-things/10-things-you-have-to-know-to-be-computer-literate/

Stauffer, B. (2020, April 16th). How to Teach Digital Literacy Skills. Applied educational system. Retrieved from https://www.aeseducation.com/blog/teach-digital-literacy-skills

What is digital literacy? (2020, January 15th – Last Update). Western Sydney University. Retrieved from https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/studysmart/home/digital_literacy/what_is_digital_literacy

Official documents

Council of Europe (COE) (2011). “Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Structured overview of all CEFR scales”. Retrieved from http://ebcl.eu.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/CEFR-all-scales-and-all-skills.pdf

Council of Europe (n.d.). Self-assessment grid – Table 2 (CEFR 3.3): Common Reference levels. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/table-2-cefr-3.3-common-reference-levels-self-assessment-grid

What are comics? Get yourself acquainted with different styles!

|

Duration: 60 minutes Objectives: The objective of this lesson is to introduce learners to the world of comics and its diversity. Learners will familiarize themselves with the history of the genre, its definitions, and its multiple forms. Desirable outcomes and competences: By the end of the lesson, learners should be able to:

|

The impossible definition

When it comes to comics, defining it accurately is one of the hardest tasks. Each researcher has his/her own definition, and in the literature, no one seems to agree. Therefore, we believe it is necessary to give you a little bit of context so that you can forge your own idea.

Comics’ history starts early. Way earlier than anybody might think. This is at least the opinion of Perry and Aldridge (1967), in their “Penguin Book of Comics”. They consider the first comic to be Bayeux Tapestry, a medieval masterpiece narrating the story of the Conquest of England by William The Conqueror. ‘How is that possible?’, you might ask?

Check it out:

Bayeux Tapestry c. 1066 – 1082, Museum of Bayeux Tapestry. (Source: Museum of Bayeux Tapestry)

The drawings do not stand alone: most of them come with a text in Latin written above the characters, explaining them. That is why Perry and Aldridge (1967) consider this tapestry to be one of the first comics. A story is narrated by a succession of drawings, helped by a few captions, included within the drawings themselves.

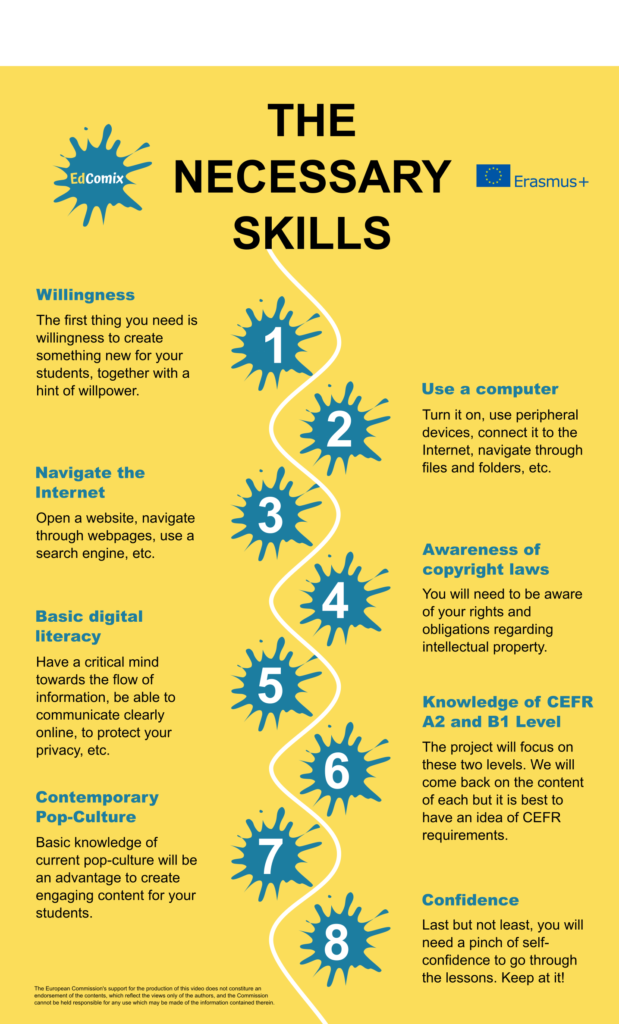

Stained-glass window, Notre-Dame de Paris, (Source: Hammer, n.d.)

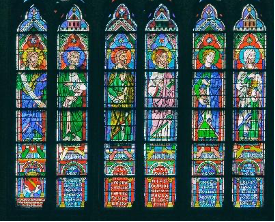

Stele of Maâty, c. 2051-2031 BC, NY: MOMA, (Source: Charlet, n.d.)

Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus, Lybia. (Source: Gallouzi, n.d.)

Now, let’s leave the 11th century and rewind time slightly more. Based on the above idea, could you think of three ancient techniques or art forms that could be added to our soon-to-be definition?

Cave paintings. Hieroglyphs. Stained-glass windows. Similarly to comics, they are series of ‘drawings’ made to tell stories.

Despite this, it has been generally accepted not to include them in the comics’ definition. Instead, a new category was created: sequential arts, which include comics, as well as the three previous examples.

This expression was introduced by Will Eisner in 1985 in his book “Comics and Sequential Arts”. However, Eisner did not give a clear definition of his new concept. Scott McCloud was the first to offer one. According to him, sequential arts are “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the reader” (McCloud, 1997). Inclusive of both comics and cave paintings, among others, this definition will be used throughout this project, as we do not wish to exclude it. Nonetheless, bear in mind that it is not accepted as a definition for comics.

Here is another definition, from Kunzle (1973):

“Of any period, in any country:

- There must be a sequence of separate images;

- There must be a preponderance of image over text;

- The medium in which the comic appears and for which it is originally intended must be reproductive, that is, in printed form, a mass medium;

- The sequence must tell a story which is both moral and topical.”

This definition appears in “History of the Comic Strip Volume 1” and has been strongly criticized. According to Groensteen (2007), the third point only serves the author’s interest, to justify his choice to start the analysis of his book in 1450, with the invention of printing.

You might start to grasp the complexity of the defining process here. Like any arts, comics evolve following artists’ imagination. Groensteen (2009) has even published a 7-page article on the impossibility of defining correctly what a comic is.

What adds to the confusion is that some authors of comics might describe their work as “cartoons” or “comics”, depending on whether they find one or the other demeaning or not.

A short history of comics

As you might guess, having such troubles defining and determining which art or techniques to include, makes it equally complicated to find a starting point to comics’ history. Most sources agree on the 1930s. The year 1933 to be exact, with the publication of what is considered to be the first comic book. (Yıldırım, 2013)

While popular in the 1940s, comics’ reputation plunged in the 1950s following vilifying publications. Teachers, who had started bringing them in their classrooms, stopped to do so in the US. For more than thirty years and up until the 1990s, this art will be the preserve of children, young adults, and fans.

Like every art type, comics have their styles and ages. For an extensive description of each age, we invite you to read our Pedagogical Guide (IO1).

Comics’ main characteristics

Still, we understand that you might need to give a definition to your students. Therefore, we will quickly go over what is traditionally understood as being constitutive of comics: their main characteristics.

- Narrative: Humoristic or serious, comics have a narrative transcribed in both text and drawings, both participating in the general understanding of the story, although visuals are usually more prominent than text. Their interdependence is what distinguishes them. Comics ‘bridge the gap’ between textual and visual media (Muzumdar, 2016). Nevertheless, it has been highlighted several times that some comics do not have text, which does not keep them from being considered as such.

- Panels: Narrative is presented in boxes, named panels. They act as a general indicator of time and space. Their disposition throughout the page differentiates them from moving pictures. Within films, pictures are placed one after the other in time. Within comics, they are placed one after the other in space. As Yang (2008) describes it, comics are permanent. They allow the reader to integrate information at theirown pace, reading the panels in order or going back to previous panels, whereas movies are time-bound and can only be watched moving forward.

For an in-depth description of comics’ components and structure, you can check out lesson 11.

Main types of comics

Now that we have been over the technicalities of the definition, it is time to discover the forms that comics take.

A comic strip

A comic strip is formed by a minimum of two panels. This is the shortest form it can take. Often humoristic, from three to five panels long, it is mostly seen in newspapers and magazines.

This is the easiest form to use in the classroom. Its concise format allows it to be added to any lesson. You can find one premade or create it yourself, using a variety of tools. We detail comics creation steps in Part 3 of this module.

You could consider including them in several lessons, to give a visual explanation to complicated notions or to include them as an exercise or as a group activity. Many possibilities and activity examples will be described in Lesson 9.

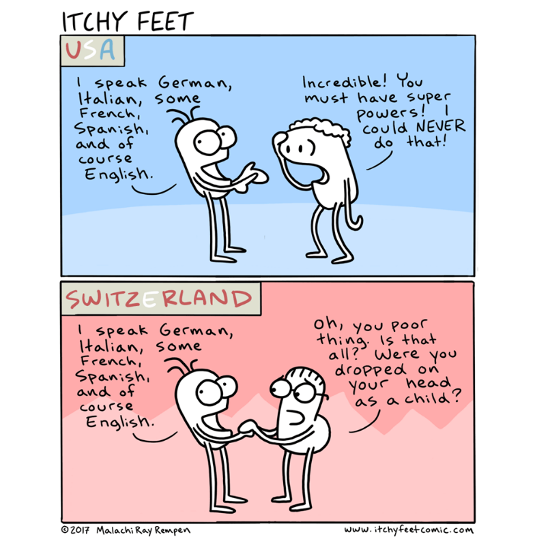

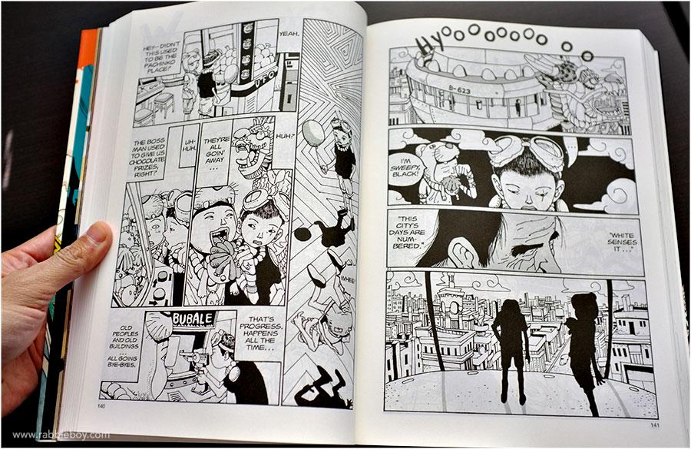

Source: Rempen, 2018

Below are two examples of a comic strip series that could be fun in language and culture classes. The author calls himself “Itchy feet” and regularly publishes humorous comics dealing with the difficulties of language learning, cultural adaptation, and traveling. They are all available on his blog: http://www.itchyfeetcomic.com/

A comic book

A comic book or album consists of several pages and is usually divided into several albums.

To include them into your classroom, you could consider educational comics. They can be subdivided into two categories:

i. Comics created to be educational: They are created by teachers, for teachers and usually focus on one subject of the curriculum.

Source: Rickert, n.d.

Here is an extract of an educational comic book, focused on English grammar. The author, David Rickert, is a high school English teacher in the United States.

ii. Regular comics that turned out to have an educational perspective. For more information, check our pedagogical guide, available for free on the EdComix website. There, we argue that most comics can be used as educative material, especially in language acquisition. The hardest part will be to choose one.

A graphic novel

Introduced by Will Eisner, this expression has a complicated definition, similarly to comics. Some authors consider it to be a lengthier version of comic books where the entire story is contained within one publication (Ásbjörnsson, 2018). Others consider the term as a synonym and a way to wash comics’ bad reputation.

If you follow the first definition, graphic novels are easier to use in the classroom. One could be featured as a recurring home-study exercise, followed by an analysis in the classroom. As they come in one whole publication, they are more affordable and they feature a complete story.

A manga

The term can be roughly translated from Japanese as “whimsical pictures”. It corresponds to a style of Japanese comic books, read from right to left, that has been developing since the late 19th century (Asher and Sola, 2011). They differ from comic books mostly in their graphic style.

Mangas can be practical in the classroom. They offer a more affordable alternative to comic books and graphic novels and will introduce variety. Educational manga is a fully-fledge category. The collection “The Manga Guides”, published by Masaharu Takemura (2003 – present) is a good example. Here is an extract from “The Manga Guide to Molecular Biology” (2009).

Source: Takemura, 2009, p.9

However, keep in mind that manga are read from right to left, unless the pages have been reversed, as it was sometimes done when mangas were published in Europe in the 1990s. In addition, as Japanese reads from top to bottom, bubbles tend to be narrow and vertical, which makes the distribution of words in languages written in letters a challenge. We can see that the example above was created in English as the bubbles are horizontal and not vertical. In the setup of a dys-friendly class, we would advise using regular ‘western-style’ comic books to avoid any additional challenge. The only exception to this would be, of course, if your students are fans of a franchise, which can encourage them to go the extra mile to read their favourite series.

A webcomic

They are regular comics strips or books taking advantage of the opportunities offered by the Internet and digital media. As they spread widely, a new form was born: motion comics.

In this case, nothing beats a visual explanation. Click here to discover an example by Warner Bros Pictures (2016) on YouTube.

References

-

Books

Eisner, W. (1985). Comics and Sequential Art. Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press.

Groensteen, T. (2007). The system of Comics. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Retrieved from https://books.google.fr/books?id=tgNKwRM00w0C&printsec=frontcover&hl=fr&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Groensteen, T. (2009). The impossible definition, in Heer, J. and Worcester, K. (Ed.), A comic study reader (pp.124 – 131). Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Retrieved from https://books.google.fr/books?id=9LUYhG9qO_8C&dq=definitions+of+comics&lr=&hl=fr&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Kunzle, D. (1973). The early comic strip: Narrative Strips and picture stories in the European broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825. Berkeley: University of California Press.

McCould, S. (1997). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. NYC: William Morrow

Perry, G. and Aldridge, A. (1967). The Penguin Book of Comics. London: Penguin Books.

Takemura, M. (2009). The Manga Guide to Molecular Biology. San Francisco, CA: No Starch Press.

-

Articles

Muzumdar, J. (2016). An Overview of Comic Books as an Educational Tool and Implications for Pharmacy. Inov Pharm. 7(4). 1 – 10. Retrieved from http://pubs.lib.umn.edu/innovations/vol7/iss4/1

Yang, G. (2008). Graphic Novels in the Classroom, Language Arts, 85, pp.185-192. Retrieved from https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/LA/0853-jan08/LA0853Graphic.pdf

Yıldırım, A. H. (2013). Using Graphic Novels in the Classroom, Journal of Language and Literature Education, 8, 118-131, Retrieved from http://oaji.net/articles/2014/1069-1406114482.pdf

-

Websites

Asher, J., and Sola, Y., (2011). The Manga phenomenon. WIPO Magazine, 5. Retrieved from https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2011/05/article_0003.html

-

Thesis and dissertations

Ásbjörnsson, J. M., (2018). On the Use of Comic Books and Graphic Novels in the Classroom [B.A. Thesis, University of Iceland]. Retrieved from https://skemman.is/bitstream/1946/30300/7/Jo%CC%81n%20Ma%CC%81r%20BA%20final%20skil%20revised%201%20final%201.pdf

-

Video-based sources

Warner Bros Pictures, (2016). The Accountant – Motion Comic [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YF_labM9Jp4

-

Images

Charlet J-J. (Photograph, n.d.). Stele of Maâty, c. 2051-2031 BC, NY: MOMA [Picture]. Projet Rosette. http://projetrosette.info/page.php?Id=799&TextId=51&langue=FR&fbclid=IwAR3Z5q5NN_PzuECFnnY1lSB-vzt_sooTUZaS2CQBV23kHWgfe7_1L7hU3Uw

Galuzzi L. (Photograph, n.d.). Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus, Lybia [Picture]. Heritage daily.https://www.heritagedaily.com/2020/03/10-prehistoric-cave-paintings/126971

Hammer V. (Photograph, n.d.). Stained-glass window, Notre-Dame de Paris [Picture]. Unsplash.https://unsplash.com/@derveit?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditCopyText

Museum of Bayeux Tapestry (n.d.). Bayeux Tapestry c. 1066 – 1082 [Picture], Museum of Bayeux Tapestry. bayeux.fr

Rempen M.R (2018), Itchy feet. itchyfeetcomic.com

Rickert D. (n.d.), Grammar comics, E-book, Available here.

-

Media and Techniques

Itchy feet, various comics strips, available at http://www.itchyfeetcomic.com/

Rickert D. (n.d.), Grammar comics, E-book available at https://penningtonpublishing.com/products/grammar-comics

Collection The Manga Guides (2003- Present), San Francisco, CA: No Starch Press

Garcia, S. (2015), On the Graphic Novel. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. retrieved from https://books.google.fr/books?id=Yth0CgAAQBAJ&dq=sequential+art+eisner+definition&hl=fr&source=gbs_navlinks_s

COMICS AND DIFFERENT ASPECTS OF INCLUSION

Duration: 70 minutes Objectives: The objective of this lesson is to get learners familiar with the different aspects of inclusion in comics, in order to make adaptations to reach a larger and more diverse audience in the classroom. These aspects are referring to socio-economic challenges and cultural practices, but also learning difficulties due to Specific Learning Disorders (SLD). Desirable outcomes and competences: By the end of the lesson, learners should be able to:

|

Inclusion refers to accessible material for learners with respect to their cultural diversity, but also to an adaptive pedagogical content and approach to teaching and learning for people with Specific Learning Disorders.

Socio-economic diversity

Comics are cultural media or products that create stories. These stories are related to a cultural context that is in a specific setting, time, and with preconceived ideas or references that the audience must be equipped with to understand. Accordingly, comics cannot be neutral as they carry ideas and beliefs that could be identified as misleading, stereotypical, or biased.

Following the previous lessons about the definition, origins and different types of comics, one can immediately presume that each type or genre has their own codes and structures as well as cultural references, that allow readers to understand them. For instance, we can see the differences in the three big categories of origin of comics: Western European, American and Manga. Comics of these categories have obvious cultural differences that reflect in their format, style, content and codes of references such as jokes, use of language and rhythm of narration. This cultural diversity has references in different cultures and social standards that could create stereotypes on the socio-economic status of each culture.

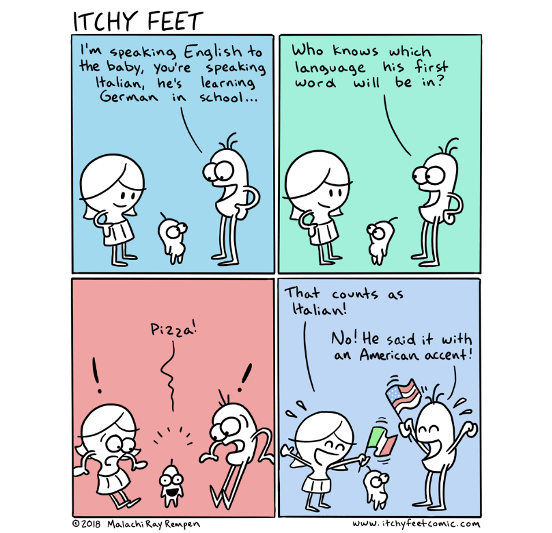

Image 1: Example of American comics. Source: comicskingdom.com

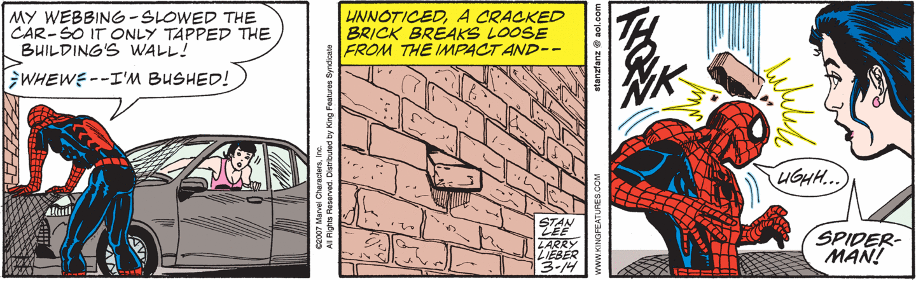

Image 2: Example of Manga book. Source: rabbleboy.co

To be inclusive in terms of diverse socio-economic and cultural backgrounds, it is advised mixing different genres and types of comics, e.g. American comics alongside European classics, and online comic strips and or innovative forms of comics, allowing learners to observe and explore the differences and the commonalities. Using a variety of different types of comics is the key not only to keeping your students motivated, but also to exploring and experimenting with different styles and formats and information about cultural backgrounds.

In addition, learners should be open-minded and aware that there is not one ‘better’ category or genre of comics than another, for instance it would be wrong to claim that “European comics are better than manga”. In fact, this statement hides many prejudices about each other’s culture. Learners should be able to discover and select their preference, from the large variety of comics that provide a unique exploration about other cultures and social backgrounds.

Diversity in representation in comics

Inclusivity also refers to social and cultural diversity in terms of representation in comics. This means to acknowledge representation related to gender, race, disabilities, cultures, religions or other identities or groups of people in general (e.g. smart people, strong people, etc). Because comics convey ideas about what or who can be represented and how and, therefore, the words and images used can include or exclude audiences, even without intention. Hence, representation of different groups matters and can offer challenges and opportunities in terms of inclusion.

For this reason, it is essential to validate the cultural context of the comics used in the classroom, as with any other material, and, specifically, take care of diversity in the characters on a cultural, social, gender and ability level. The general public but especially educators, who are interested in comics and comic creation for their classrooms, should take into account this dimension of inclusion in order to avoid reproducing and spreading clichés and biased opinions about different cultures. Specifically, attention should be paid to the following three axes:

Gender

Comics have a richer panel of male tropes than women and this creates an inequality in terms of gender balance. We can easily name a male comic hero’s name and identity, but it takes a couple of minutes more to name a female hero or main character of a story. This should be addressed, and teachers should encourage students to avoid using the stereotypical roles of women and men in a society (e.g.: woman in charge of the house and family and a working man). Nonetheless, negative representations of gender do not only apply to women. The male characters are in most cases athletic and likeable, which sets difficult and sometimes impossible standards for boys to reach or simply to identify with. In conclusion, regarding gender issues, we would greatly advise teachers to make sure that they include several roles and types of women and men in the comics.

Social Status

Representation of groups from diverse social status is crucial for avoiding creating inequalities that can be perceived as actual differences in the treatment of people. Characters should vary in social status and level of public recognition, so that learners have different reference points for different roles and functions in society. Nevertheless, one should avoid clichés and integrate diverse roles in different situations within a story.

Race

It is essential to deal with misrepresentations or misperceptions of racial and cultural stereotypes and prejudices. As many stories, comics can also convey a negative image of an ethnicity or culture. This also includes ethnocultural and religious practices, as well as observances and other customs which express the ‘identity’ of the race. Teachers should introduce the comic with its historical context, which will allow students to understand why it presents some items or characters in a certain way. Also, conducting research on the background and cultural meanings of a story enables teachers to understand, clarify and provide justified explanations about the context, and make sure it would be understood in an appropriate way by the audience or reader.

Disability

When it comes to inclusive representation in comics, we also refer to disabilities. Main characters could represent people with different types of disability. For instance, a girl with hearing problems or a boy in a wheelchair could be good examples of diverse characters and heroes of a story. This might set an example for a more inclusive mindset as well as help students who have a disability or disorder.

Specific Learning Disorders (SLD)

Another aspect of inclusion refers to adaptations for learners with Specific Learning Disorders, SLD for short. SLDs are disorders that are diagnosed in 10 to 12% of the population, according to numbers provided by the French Federation of Dys and the European Dyslexia Association. They can have several causes, among which researchers have identified a neurobiological cause that affects the way the brain processes information. In fact, SLDs might be caused by a combination of difficulties in the cognitive development of abilities like phonological processing, working memory, rapid naming, sequencing, and the automaticity of basic skills. It is however not at all linked with the level of intelligence, any existing motor disability nor with any sensory disability such as visual or hearing impairment.

Different types of SLD and their difficulties

Most SLDs use the affix ‘dys’ to signify the partially lacking ability, like dyslexia for instance. They often overlap, thus creating a combination of difficulties in the learning process. Here is a short explanation of these disorders and the difficulties they cause:

Dyslexia: is a cognitive disorder that causes difficulties in reading comprehension and language-based processing skills. The dyslexic brain takes longer to identify and connect letters and words with other kinds of knowledge, for example translating them into sounds.

Dyspraxia: refers to difficulties with movement and coordination, language and speech. It is characterized by difficulty in muscle control (including eye control), which causes problems with movement and coordination, language and speech, and can affect learning. This disorder however is usually classified as a Developmental Coordination Disorder and not as a specific learning disorder, but we will address it nevertheless, as it impacts the learning process and education as well.

Dyscalculia: affects a person’s ability to understand numbers and learn math facts. Individuals in the case of dyscalculia, may have poor comprehension of math symbols and struggle with memorizing and organizing numbers. This is noticeable for instance when facing difficulties in telling the time or with counting.

Dysphasia: typically involves difficulties with speaking and understanding spoken words. The symptoms cannot be attributed to sensorimotor, intellectual deficits, autism spectrum, or other developmental impairments. Likewise, it does not occur as

the consequence of an evident brain lesion or as a result of the child’s background.

Dysgraphia: affects a person’s ability in handwriting and fine motor skills. Specifically, a dysgraphic person may encounter problems such as illegible handwriting, inconsistent spacing, poor spatial planning on paper, poor spelling, and difficulty composing writing as well as thinking and writing at the same time. This disorder is often confused with dyslexia as both disorders affect the writing ability.

Recommended adaptations

For all the above learning disorders, educators are advised to adapt the learning material and content to meet the specific needs and requirements for inclusive education for students with SLDs.

Below we list the General Adaptations of written material which can be beneficial also for regular education students as well:

- Use text font types such as Arial, Century Gothic or OpenDys. Other options could be Verdana, Tahoma, Open Sans, Century Gothic or Trebuchet.

- Opt for adapted spacing of 1,5 in between the lines, in a font size that should range between 12 and 14.

- Align the text to the left but do not justify it.

- Print on one side as it helps students to avoid the manipulation of having to turn pages.

- Use colours to separate information and be consistent in the colour codes.

- Use off-white or pastel coloured paper whenever possible.

Adaptations in comic material rely on students’ visual ability for processing information. In this context, we list below the Specific Adaptation for comics to support learners with SLDs:

Text

It is important to choose a text font that learners with SLDs will be comfortable with. Among those, for digital comics we recommend using Sans Serif fonts such as Arial and Comic Sans.

Be consistent in either using all capital letters (ALL CAPS) that is very common in comics anyway, or normal capitalization. Using ALL CAPS allows one to fit more dialogues into less space and keep it clear, so it is better for visual readers or students with SLDs.

Avoid the use of italics or bold italics but also underlining. For emphasis, the word could be highlighted or turned into different colours.

Finally, numbers generally should always be spelled out, unless they are a date, designation, part of a name or a larger number.

Panels

An adapted comic panel should be large enough and with a clear outline, to help the ‘dys’ reader distinguish between the different actions and scenes.

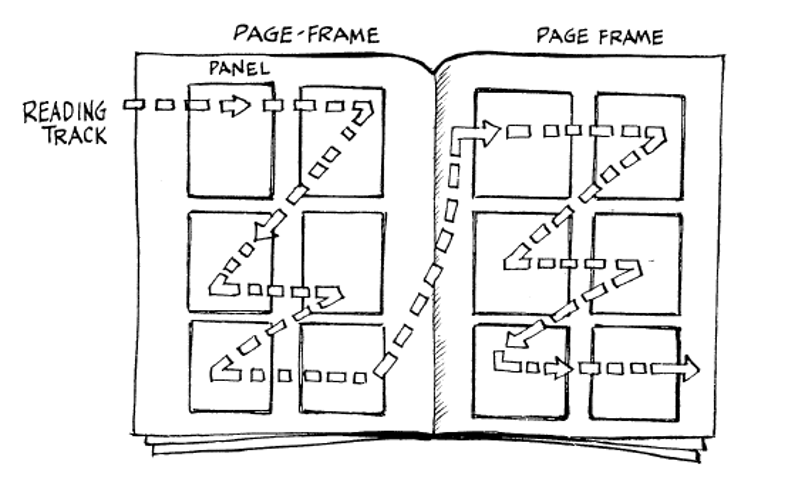

The panel strips are essential for making the student conscious of the page organisation. Hence, the order of the panels should be adapted to help pupils with SLDs navigate through the different panels and be able to follow the storyline. For example, for younger readers it could have arrows with directions to show where the story is going to. Accordingly, the panels should follow a left to right order (for western countries), aligned, with a clear order and consistent shapes and sizes across the pages.

Image 3 – Panel reading track (3)

Source: Eisner W. (1985), Comics and Sequential Art

A controversial example of this would be the case of the Japanese comics (manga), which have an opposite orientation and, thus, can be challenging at first for western ‘dys’ readers.

Bubbles and speech framing

The comic bubble or balloons can vary in shapes and styles, as long as they stay consistent through all the comic strip; but it is important to have enough space inside the bubbles for the text to fit, avoiding the use of hyphenating to break the word. Also, balloons should not overlap with each other or with the frame of the panel. On the other hand, having joint balloons is not considered problematic, especially since it allows to break text into more digestible pieces of information.

The text inside a balloon reads also from left to right and top to bottom in the western countries, and in relation to the position of the speaker. For students with SLDs, it is important to use balloons tails to indicate which character is speaking by pointing to the character’s mouth.

Graphic Design and Illustrations

To facilitate reading for pupils with SLD, a good quality of image, as well as printing in paper version, should be ensured. Intense graphics and use of many bright colours should be avoided, but colour contrast (black and white) and a clear outline is always a safe design. Furthermore, attention should be paid to the distance of image and text; that is not to be too far away so the reader can make the links easily.

References

Books

Byrne R. (2014, January 13). Free Ebook – Digital Storytelling With Comics. Free technology for teachers. https://www.freetech4teachers.com/2014/01/free-ebook-digital-storytelling-with.html

Cohen, M.J. & Sloan, D.L. (2007). Visual supports for people with autism: A guide for parents and professionals. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House, Inc.

Eisner W. (1985), Comics and Sequential Art, Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press

Garcia S. (2015), On the Graphic Novel, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, retrieved from https://books.google.fr/books?id=Yth0CgAAQBAJ&dq=sequential+art+eisner+definition&hl=fr&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Hamilton, M., & Weiss, M. (2005). The Power of Storytelling in the Classroom, Excerpt from Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom 2/e.

McWilliams, B. (n.d.). Effective Storytelling A manual for beginners. https://www.eldrbarry.net/roos/eest.htm

Vlahos, J. (2018, September 27). The Ultimate Guide to Comic Book Font. Retrieved from https://www.printi.com/blog/comic-book-font/

Articles

Dettinger C. (2013) “Using Visual Supports with Students Accessing an Adapted Curriculum”. Education 589 Projects. 11. https://scholar.umw.edu/education_589/11

Does Comic Sans help dyslexic learners? (2018, January 21). The Times Educational Supplement. Retrieved July 1, 2020, from https://www.tes.com/news/does-comic-sans-help-dyslexic-learners

Greenfield, D. (2018, June 20). 13 Visual Storytelling Tips For Comics. 13th Dimension. https://13thdimension.com/13-visual-storytelling-tips-for-comics/

McManis, L.D. (n.d.). TIPS FOR TEACHERS AND CLASSROOM RESOURCES. Inclusive Education: What It Means, Proven Strategies, and a Case Study. https://resilienteducator.com/classroom-resources/inclusive-education/

Moody, A.K. (2012). Family Connections: Visual supports for promoting social skills in young children: A family perspective. Childhood Education, 88(3), 191-194. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2012.682554

Yang G. (2008), Graphic Novels in the Classroom, Language Arts, 85, pp.185-192. Retrieved from https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/LA/0853-jan08/LA0853Graphic.pdf

Website

Blambot.com Comic Book Grammar & Tradition [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blambot.com/pages/comic-book-grammar-tradition

MOOCDys website: https://www.moocdys.eu/

Video-based sources

Library of American Comics (2020), The LOAC Story [Video], Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIJvS1wmDEk

Understood (2018, September 7), Thriving with Dyslexia: Rossie Stone & Dekko Comics [Video], Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DnTiPdzrw_o&t=180s

Images

Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, and Alex Saviuk’s Amazing Spider-Man (March 14, 2007). Source: comicskingdom.com

Taiyo Matsumoto (1994), Tekkon Kinkreet Black & White. Source: rabbleboy.com

Eisner W. (1985), Comics and Sequential Art, Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press. p.41

This project (2019-1-FR01-KA201-062855) has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.